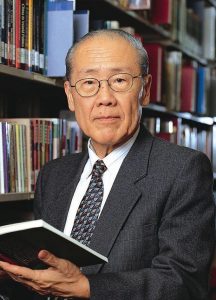

Modern China has been torn between affirming the integrity of its history despite the Sinocentric biases and accepting world history in the Eurocentric tradition. This ambivalence has not helped other people to understand China’s position in world history. Why this ambivalence? China obviously does not wish to accept a narrative that reads history backward, to take European history since the 17th and 18th centuries as norm. Together with other peoples with a strong heritage of their own past, the Chinese think it is unhistorical to impose one dominant narrative upon everyone’s past.

Modern China has been torn between affirming the integrity of its history despite the Sinocentric biases and accepting world history in the Eurocentric tradition. This ambivalence has not helped other people to understand China’s position in world history. Why this ambivalence? China obviously does not wish to accept a narrative that reads history backward, to take European history since the 17th and 18th centuries as norm. Together with other peoples with a strong heritage of their own past, the Chinese think it is unhistorical to impose one dominant narrative upon everyone’s past.

Wang Gengwu, The Renewal: The Chinese State and the New Global History

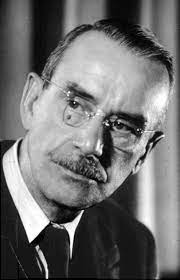

The nation, too, is not only a social but also a metaphysical being; the nation, not “the human race” as the sum of the individuals, is the bearer of the general, of the human quality; and the value of the intellectual-artistic-religious product that one calls national culture, that cannot be grasped by scientific methods, that develops out of organic depth of national life–the value, dignity and charm of all national culture, therefore, definitely lies in what distinguishes it from all others, for only this distinctive element is culture, in contrast to what all nations have in common, which is only civilization. Here we have the difference between individual and personality, civilization and culture, social and metaphysical life. The individualistic mass is democratic, the nation aristocratic.

Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man

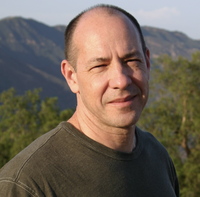

Above all, by dramatizing the violent and destructive process by which these archaic societies are transformed by and incorporated into the modern world, these four novelists (Hardy, Conrad, Achebe, and Llosa) testify to the havoc wreaked upon individual human lives in the name of progress. The novelists I discuss are all citizens and beneficiaries of the modern world, but they nonetheless felt compelled to record for posterity the great costs, paid in blood and pain, the peoples around the world have rendered to settle accounts with history.

Above all, by dramatizing the violent and destructive process by which these archaic societies are transformed by and incorporated into the modern world, these four novelists (Hardy, Conrad, Achebe, and Llosa) testify to the havoc wreaked upon individual human lives in the name of progress. The novelists I discuss are all citizens and beneficiaries of the modern world, but they nonetheless felt compelled to record for posterity the great costs, paid in blood and pain, the peoples around the world have rendered to settle accounts with history.

Michael Valdez Moses, The Novel and the Globalization of Culture

The problems of interpretation facing an intralingual critic are formidable enough: they become doubly so for the interlingual critic, since to the problems due to differences between historical periods are added those due to cultural and linguistic differences. The interlingual critic has to make a decision as to what basic attitude he should take toward such differences, and the decision will determine the kind of interpretation that he will offer. It is not an easy decision to make, for even within a single cultural and literary tradition there can be conflicting schools of hermeneutics. . . . With regard to the interpretation of Chinese literature, the critic has a similar set of attitudes to choose from: Sino-centrism, Eurocentrism, cultural relativism, cultural perspectivism and trans-culturism. I am avoiding the term “cultural chauvinism” or “ethnocentrism” so that the critic’s own cultural and ethnic identity need not be called into question.

The problems of interpretation facing an intralingual critic are formidable enough: they become doubly so for the interlingual critic, since to the problems due to differences between historical periods are added those due to cultural and linguistic differences. The interlingual critic has to make a decision as to what basic attitude he should take toward such differences, and the decision will determine the kind of interpretation that he will offer. It is not an easy decision to make, for even within a single cultural and literary tradition there can be conflicting schools of hermeneutics. . . . With regard to the interpretation of Chinese literature, the critic has a similar set of attitudes to choose from: Sino-centrism, Eurocentrism, cultural relativism, cultural perspectivism and trans-culturism. I am avoiding the term “cultural chauvinism” or “ethnocentrism” so that the critic’s own cultural and ethnic identity need not be called into question.

James J.Y. Liu, The Interlingual Critic

But in India, it [despotism] is normal: for here there is no sense of personal independence with which a state of despotism could be compared, and which would raise revolt in the soul; nothing approaching even a resentful protest against it, is left, except the corporeal smart, and the pain of being deprived of absolute necessaries and of pleasure. In the case of such a people, therefore, that which we call history is not to be looked for. … This [Hinduism] makes them incapable of writing history; all that happens is dissipated in their minds into confused dreams.

But in India, it [despotism] is normal: for here there is no sense of personal independence with which a state of despotism could be compared, and which would raise revolt in the soul; nothing approaching even a resentful protest against it, is left, except the corporeal smart, and the pain of being deprived of absolute necessaries and of pleasure. In the case of such a people, therefore, that which we call history is not to be looked for. … This [Hinduism] makes them incapable of writing history; all that happens is dissipated in their minds into confused dreams.

Georg Wilhelm Frederick Hegel, The Philosophy of History

Appeals to the past are among the commonest of strategies in interpretations of the present. What animates such appeals is not only disagreement about what happened in the past and what the past was, but uncertainty about whether the past really is past, over and concluded, or whether it continues, albeit in different forms, perhaps. This problem animates all sorts of discussions—about influence, about blame and judgment, about present actualities and future priorities. … The relatively common denominator between the various aspects of Orientalism is the line separating Occident from Orient and this is less a fact of nature than it is a fact of human production, which I have called imaginative geography. This is, however, neither to say that the division between Orient and Occident is unchanging nor is it to say that it is simply fictional.

Appeals to the past are among the commonest of strategies in interpretations of the present. What animates such appeals is not only disagreement about what happened in the past and what the past was, but uncertainty about whether the past really is past, over and concluded, or whether it continues, albeit in different forms, perhaps. This problem animates all sorts of discussions—about influence, about blame and judgment, about present actualities and future priorities. … The relatively common denominator between the various aspects of Orientalism is the line separating Occident from Orient and this is less a fact of nature than it is a fact of human production, which I have called imaginative geography. This is, however, neither to say that the division between Orient and Occident is unchanging nor is it to say that it is simply fictional.

Edward Saïd, Orientalism Reconsidered

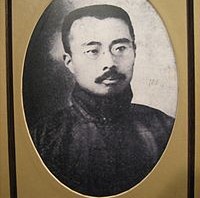

For instance, the Frenchman Maupassant’s Une Vie is human literature about the animal passions of man; China’s Prayer Mat of Flesh, however, is a piece of non-human literature. The Russian Kuprin’s novel Jama is literature describing the lives of prostitutes, but China’s Nine-tailed Tortoise is non-human literature. The difference lies merely in the different attitudes conveyed by the work, one is dignified and one is profligate; one has aspirations for human life and therefore feels grief and anger in the face of inhuman life, whereas the other is complacent about human life, and the author even seems to derive a feeling of satisfaction from it, and in many cases to deal with his material in an attitude of amusement and provocation. In one simple sentence: the difference between human and non-human literature lies in the attitude that informs the writing; whether it affirms human life or inhuman life.

For instance, the Frenchman Maupassant’s Une Vie is human literature about the animal passions of man; China’s Prayer Mat of Flesh, however, is a piece of non-human literature. The Russian Kuprin’s novel Jama is literature describing the lives of prostitutes, but China’s Nine-tailed Tortoise is non-human literature. The difference lies merely in the different attitudes conveyed by the work, one is dignified and one is profligate; one has aspirations for human life and therefore feels grief and anger in the face of inhuman life, whereas the other is complacent about human life, and the author even seems to derive a feeling of satisfaction from it, and in many cases to deal with his material in an attitude of amusement and provocation. In one simple sentence: the difference between human and non-human literature lies in the attitude that informs the writing; whether it affirms human life or inhuman life.

Zhou Zuoren, Humane Literature

Nations, like narratives, lose their origins in the myths of time and only fully realize their horizons in the mind’s eye. Such an image of the nation–or narration–might seem impossibly romantic and excessively metaphorical, but it is from those traditions of political thought and literary language that the nation emerges as a powerful historical idea in the West. … A nation is a soul, a spiritual principle. Two things, which in truth are but one, constitute this soul or spiritual principle. One lies in the past, one in the present. One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories; the other is present-day consent, the desire to live together, the will to perpetuate the value of the heritage that one has received in an undivided form. Man does not improvise. The nation, like the individual, is the culmination of a long past of endeavors, sacrifice, and devotion. . . . A nation is therefore a large-scale solidarity, constituted by the feeling of the sacrifices that one has made in the past and of those that one is prepared to make in the future. It presupposes a past; it is summarized, however, in the present by a tangible fact, namely, consent, the clearly expressed desire to continue a common life. A nation’s existence is, if you will pardon the metaphor, a daily plebiscite, just as an individual’s existence is a perpetual affirmation of life.

Nations, like narratives, lose their origins in the myths of time and only fully realize their horizons in the mind’s eye. Such an image of the nation–or narration–might seem impossibly romantic and excessively metaphorical, but it is from those traditions of political thought and literary language that the nation emerges as a powerful historical idea in the West. … A nation is a soul, a spiritual principle. Two things, which in truth are but one, constitute this soul or spiritual principle. One lies in the past, one in the present. One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories; the other is present-day consent, the desire to live together, the will to perpetuate the value of the heritage that one has received in an undivided form. Man does not improvise. The nation, like the individual, is the culmination of a long past of endeavors, sacrifice, and devotion. . . . A nation is therefore a large-scale solidarity, constituted by the feeling of the sacrifices that one has made in the past and of those that one is prepared to make in the future. It presupposes a past; it is summarized, however, in the present by a tangible fact, namely, consent, the clearly expressed desire to continue a common life. A nation’s existence is, if you will pardon the metaphor, a daily plebiscite, just as an individual’s existence is a perpetual affirmation of life.

__________Homi Bhabha, Nation and Narration

In Western Europe during the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries, there was individualism that was responsible for today’s civil world, built by countless people who loved freedom more than bread, and who cared more about truth than their own life. Now some say to you, “Sacrifice your personal freedom to fight for the freedom of the nation!” But I say to you: “Fighting for your own individual freedom is fighting for the freedom of your nation! To fight for your own dignity is to fight for the dignity of the nation! A nation of freedom and equality cannot be built by a group of slaves.

_____Hu Shi, Introducing My Own Thinking 1930;.

The ubiquitous potential presence of a balanced, totalized, dimension of meaning may partially explain why a fully realized sense of the tragic does not materialize in Chinese narrative. …. But in each case the implicit understanding of the logical interrelation between these fictional characters’ particular situation and the overall structure of existential intelligibility serves to blunt the pity and fear the reader experiences as he witnesses their individual destinies. In other words, Chinese narrative is replete with individuals in tragic situations, but the secure inviolability of the underlying affirmation of existence in its totality precludes the possibility of the individual’s tragic fate taking on the proportions of a cosmic tragedy. Instead, the bitterness of the particular case of mortality ultimately settles back into ceaseless alternation of patterns of joy and sorrow, exhilaration and despair, which go to make up an essentially affirmative view of the universe of experience.

The ubiquitous potential presence of a balanced, totalized, dimension of meaning may partially explain why a fully realized sense of the tragic does not materialize in Chinese narrative. …. But in each case the implicit understanding of the logical interrelation between these fictional characters’ particular situation and the overall structure of existential intelligibility serves to blunt the pity and fear the reader experiences as he witnesses their individual destinies. In other words, Chinese narrative is replete with individuals in tragic situations, but the secure inviolability of the underlying affirmation of existence in its totality precludes the possibility of the individual’s tragic fate taking on the proportions of a cosmic tragedy. Instead, the bitterness of the particular case of mortality ultimately settles back into ceaseless alternation of patterns of joy and sorrow, exhilaration and despair, which go to make up an essentially affirmative view of the universe of experience.

Andrew Plaks, Chinese Narrative

This distortion [on the part of the Twentieth-Century scholars] conveys the impression that the Chinese gender system was built upon coercion and brute oppression, which, in my view, ascribes to it at once too much and too little power. The strength of resilience of the gender system—as it unfolded in history, not on pages of codes of conduct—should be attributed to the considerable range of flexibilities that women from various classes, regions, and age groups enjoyed in practice. … The complex and ambivalent existence of women in the Confucian tradition can be illuminated only when the propensity to treat ‘Confucianism’ as an abstract creed or a static control mechanism is discarded. The Confucian tradition is not a monolithic and fixed system of values and practices. … Contrary to the popular perception that gender relations belong to the feudal backwaters, my contention is that they constitute the most enabling aspect of Chinese tradition. The contestations over the meaning of modernity today would be more meaningful if tradition were being re-imagined as a series of trade-offs, and both its strengths and weaknesses were being confronted seriously. If Chinese modernity cannot be defined as the negation of tradition, then the unusual historical moment we have witnessed–the seventeenth century–is instructive in showing how tradition can be harnessed to further untraditional goals, and how women can be incorpoerated into new ways of imagining national and local communities. In these ways, the ‘teachers of the inner chambers’ still have much to teach the Chinese nation today.

This distortion [on the part of the Twentieth-Century scholars] conveys the impression that the Chinese gender system was built upon coercion and brute oppression, which, in my view, ascribes to it at once too much and too little power. The strength of resilience of the gender system—as it unfolded in history, not on pages of codes of conduct—should be attributed to the considerable range of flexibilities that women from various classes, regions, and age groups enjoyed in practice. … The complex and ambivalent existence of women in the Confucian tradition can be illuminated only when the propensity to treat ‘Confucianism’ as an abstract creed or a static control mechanism is discarded. The Confucian tradition is not a monolithic and fixed system of values and practices. … Contrary to the popular perception that gender relations belong to the feudal backwaters, my contention is that they constitute the most enabling aspect of Chinese tradition. The contestations over the meaning of modernity today would be more meaningful if tradition were being re-imagined as a series of trade-offs, and both its strengths and weaknesses were being confronted seriously. If Chinese modernity cannot be defined as the negation of tradition, then the unusual historical moment we have witnessed–the seventeenth century–is instructive in showing how tradition can be harnessed to further untraditional goals, and how women can be incorpoerated into new ways of imagining national and local communities. In these ways, the ‘teachers of the inner chambers’ still have much to teach the Chinese nation today.

Dorothy Ko, Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China

The Bourgeois limitations in feminist theory are clearly demonstrated by its difficulty in dealing with prostitution, which is interpreted solely in outworn terms of victimization. That is, feminists profess solidarity with the “sex workers” themselves but denounce prostitution as a system of male exploitation and enslavement. I protest this trivilizing of the world’s oldest profession. I respect and honor the prostitute, ruler of the sexual realm, which men must pay to enter. In reducing prostitutes to pitiable charity cases in need of their help, middle-class feminists are guilty of arrogance, conceit, and prudery. …It is a progressive feminism that embraces and celebrates all historical depictions of women, including the most luridly pornographic. It wants mythology without sentimentality and every archetype, from mother to witch and whore, without censorship. It accepts and welcomes the testimony of men.

The Bourgeois limitations in feminist theory are clearly demonstrated by its difficulty in dealing with prostitution, which is interpreted solely in outworn terms of victimization. That is, feminists profess solidarity with the “sex workers” themselves but denounce prostitution as a system of male exploitation and enslavement. I protest this trivilizing of the world’s oldest profession. I respect and honor the prostitute, ruler of the sexual realm, which men must pay to enter. In reducing prostitutes to pitiable charity cases in need of their help, middle-class feminists are guilty of arrogance, conceit, and prudery. …It is a progressive feminism that embraces and celebrates all historical depictions of women, including the most luridly pornographic. It wants mythology without sentimentality and every archetype, from mother to witch and whore, without censorship. It accepts and welcomes the testimony of men.

Camille Paglia, Vamps and Tramps